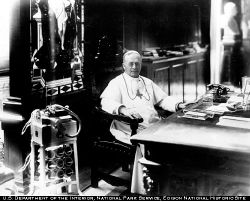

Pope Pius XI

| Pius XI | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Papacy began | 6 February 1922 |

| Papacy ended | 10 February 1939 (17 years, 4 days) |

| Predecessor | Benedict XV |

| Successor | Pius XII |

| Personal details | |

| Birth name | Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti |

| Born | 31 May 1857 Desio, Lombardy-Venetia, Austrian Empire |

| Died | 10 February 1939 (aged 81) Apostolic Palace, Vatican City |

| Other Popes named Pius | |

Pope Pius XI (Latin: Pius PP. XI; Italian: Pio XI; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939), born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti, was Pope from 6 February 1922, and sovereign of Vatican City from its creation as an independent state on 11 February 1929 until his death on 10 February 1939. He issued numerous encyclicals including Quadragesimo Anno highlighting capitalistic greed of international finance, social justice issues and Quas Primas establishing the feast of Christ the King. He took as his papal motto "Christ's peace in Christ's kingdom".

Achille Ratti had the most unusual papal career in the 20th century. Throughout his life he was an accomplished scholar, librarian and humble priest. He celebrated his 60th birthday as a priest on 31 May 1917 and fewer than five years later, on 6 February 1922, he was elected Pope, succeeding Pope Benedict XV, who was only thirty months older and thus from the same generation as Ratti. In those five years he had short stints as papal nuncio in Poland, which forced him to leave the country, and as Archbishop of Milan and Cardinal-Priest of Ss. Silvestro e Martino ai Monti, where he served for a few months before being elected Pope. He chose the name Pius, and his personality was strong, similar to Pius IX and Pius X. But as a scholar, he was open to science and research like no other Pope since Leo XIII. To establish or maintain the position of the Church, he fostered and concluded a record number of concordats including the Reichskonkordat with Germany. Under his pontificate, the 1870 stalemate concerning the Roman Question with Italy over the status of the papacy was finally solved in the Lateran Treaty of 1929 with the assistance of Cardinal Pietro Gasparri and Francesco Pacelli, brother of the future Pope Pius XII. He was unable to stop the Terrible Triangle consisting of massive Church persecution and killing of clergy in Mexico, Spain and the Soviet Union. While in Mexico and Spain, the persecution was mainly directed against the Catholic Church, hostility in the Soviet Union were directed against all Christians but especially against the Eastern Catholic Churches united with the Vatican. He vehemently protested against both Communism and National Socialism as demeaning to human dignity and a violation of basic human rights, but found no echo or support in the democracies of the West, which he labelled a Conspiracy of Silence. Against totalitarian demands, he fostered the freedom of families to determine on their own the direction of education of their children.

In one of his most important encyclicals on the social order of modern society, Quadragesimo Anno he stated that social and economic issues are vital to the Church not from a technical point of view but in terms of moral and ethical issues involved. Ethical considerations include the nature of private property.[1] in terms of its functions for society the development of the individual.[2] He defined fair wages and branded the exploitation both materially and spiritually by international capitalism. He canonized important saints including Albertus Magnus, Thomas More, Petrus Canisius, Konrad von Parzham and Don Bosco. He beatified and canonized Thérèse de Lisieux, for whom he held special reverence. He created the feast Christ the King in response to Mussolini's earthly dictatorship.

Pius XI took strong interests in fostering the participation of lay people throughout the Church, especially in the Catholic Action movement. The end of his pontificate were dominated by defending the Church from intrusions into Catholic life and education.

Public teaching: "Christ's Peace in Christ's Kingdom"

Pius XI's first encyclical as Pope was directly related to his aim of Christianising all aspects of increasingly secular societies. Ubi arcano, promulgated in December 1922, inaugurated the "Catholic Action" movement.

Similar goals were in evidence in his encyclicals Divini illius magistri (1929), making clear the need for Christian over secular education, and Casti Connubii (1930), praising Christian marriage and family life as the basis for any good society, condemning artificial means of contraception, but also acknowledging at the same time the unitive aspect of intercourse as licit:

- Any use whatsoever of matrimony exercised in such a way that the act is deliberately frustrated in its natural power to generate life is an offense against the law of God and of nature, and those who indulge in such are branded with the guilt of a grave sin.[3]

- Nor are those considered as acting against nature who in the married state use their right in the proper manner although on account of natural reasons either of time or of certain defects, new life cannot be brought forth. For in matrimony as well as in the use of the matrimonial rights there are also secondary ends, such as mutual aid, the cultivating of mutual love, and the quieting of concupiscence which husband and wife are not forbidden to consider so long as they are subordinated to the primary end and so long as the intrinsic nature of the act is preserved.[3]

Political teachings

In contrast to some of his predecessors in the nineteenth century, who had favoured monarchy and dismissed democracy, Pius XI took a pragmatic approach toward the different forms of government. In his encyclical Dilectissima Nobis (1933), in which he addressed the situation of the Church in Republican Spain, he proclaimed, that the Church is not "bound to one form of government more than to another, provided the Divine rights of God and of Christian consciences are safe", and specifically referred to "various civil institutions, be they monarchic or republican, aristocratic or democratic".[4]

Social teachings

| Part of a series of articles on Social Teachings of the Popes |

|

|

|

|

Pope Pius XI Pope Pius XII Pope John XXIII Vatican II Pope Paul VI Pope John Paul II Pope Benedict XVI General |

|

Pius XI argued for a reconstruction of economic and political life on the basis of religious values. Quadragesimo Anno (1931), was written to mark 'forty years' since Pope Leo XIII's (1878 – 1903) encyclical Rerum novarum, and restated that encyclical's warnings against both socialism and unrestrained capitalism, as enemies to human freedom and dignity. Pius XI instead envisioned an economy based on co-operation and solidarity .

Private property

The Church has a role in discussing the issues related to the social order. Social and economic issues are vital to her not from a technical point of view but in terms of moral and ethical issues involved. Ethical considerations include the nature of private property.[1] within the Catholic Church several conflicting views had developed. Pope Pius XI declares private property essential for the development and freedom of the individual. Those who deny private property, deny personal freedom and development. But, said Pius, private property has a social function as well. Private property loses its morality, if it is not subordinated to the common good. Therefore, governments have a right to redistribution policies. In extreme cases, the Pope grants the State a right of expropriation of private property.[2]

Capital and labour

A related issue, said Pius, is the relation between capital and labour and the determination of fair wages.[5] Pius develops the following ethical mandate: The Church considers it a perversion of industrial society to have developed sharp opposite camps based on income. He welcomes all attempts to alleviate these differences. Three elements determine a fair wage: the worker's family, the economic condition of the enterprise, and the economy as a whole. The family has an innate right to development, but this is only possible within the framework of a functioning economy and a sound enterprise. Thus, Pius concludes that cooperation and not conflict is a necessary condition, given the mutual interdependence of the parties involved.[5]

Social order

Pius XI believed that industrialization results in less freedom at the individual and communal level, because numerous free social entities get absorbed by larger ones. The society of individuals becomes the mass class-society. People are much more interdependent than in ancient times, and become egoistic or class-conscious in order to save some freedom for themselves. The pope demands more solidarity, especially between employers and employees, through new forms of cooperation and communication. Pius displays a negative view of capitalism, especially of the anonymous international finance markets.[6] He identifies certain dangers for small and medium-size enterprises, which have insufficient access to capital markets and are squeezed or destroyed by the larger ones. He warns that capitalist interests can become a danger for nations, which could be reduced to “chained slaves of individual interests”[7]

Pius XI was the first Pope to utilise the power of modern communications technology in evangelising the wider world. He established Vatican Radio in 1931, and he was the first Pope to broadcast on radio.

Internal Church affairs and ecumenism

In his management of the Church's internal affairs Pius XI mostly continued the policies of his predecessor. Like Benedict XV, he put a great emphasis on spreading Catholicism in Africa and Asia and on the training of native clergy in these "mission territories". He ordered every religious order to devote some of its personnel and resources to missionary work.

Pius XI continued the approach of Benedict XV on the issue of how to deal with the threat of modernism in Catholic theology. The Pope was thoroughly orthodox theologically and had no sympathy with modernist ideas that relativised fundamental Catholic teachings. He condemned modernism in his writings and addresses. However, his opposition to modernist theology was by no means a rejection of new scholarship within the Church, as long as it was developed within the framework of orthodoxy and compatible with the Church's teachings. Pius XI was interested in supporting serious scientific study within the Church, establishing the Pontifical Academy for the Sciences in 1936.

Pius XI strongly encouraged devotion to the Sacred Heart in his encyclical Miserentissimus Redemptor (1928). He canonised some important saints: Bernadette Soubirous, Therese of Lisieux, John Vianney, John Fisher, Thomas More, and John Bosco. He also named several new Doctors of the Church: John of the Cross, Albert the Great, Peter Canisius and Robert Bellarmine.

Pius XI was the first Pope to directly address the Christian ecumenical movement. Like Benedict XV he was interested in achieving reunion with the Eastern Orthodox (failing that, he determined to give special attention the Eastern Catholic churches). He also allowed the dialogue between Roman Catholics and Anglicans which had been planned during Benedict XV's pontificate to take place at Mechelen. However, these enterprises were firmly aimed at actually reuniting with the Roman Catholic Church other Christians who basically agreed with Catholic doctrine, bringing them back under Papal authority. To the broad pan-Protestant ecumenical movement he took a more negative attitude.

He condemned, in his 1928 encyclical, Mortalium Animos, the idea that Christian unity could be attained by establishing a broad federation of many bodies holding varying doctrines (the widespread view among Protestant ecumenists); rather, the Catholic Church was the one true Church, all her teachings were objectively true, and Christian unity could only be by achieved by non-Catholic denominations rejoining the Catholic Church and accepting the doctrines they had rejected.

Diplomacy

Pius XI's reign was one of busy diplomatic activity for the Vatican. The Church made advances on several fronts in the 1920s, improving relations with France and, most spectacularly, settling the Roman question with Italy and gaining recognition of an independent Vatican state.

Relations with France

France's republican government had long been strongly anti-clerical. The Law of Separation of Church and State in 1905 had expelled many religious orders from France, declared all Church buildings to be government property, and had led to the shutting down of most Church schools. Since that time Pope Benedict XV had sought a rapprochement, but it was not achieved until the reign of Pope Pius XI. In Maximam Gravissimamque (1924) many areas of dispute were tacitly settled and a bearable coexistence made possible.

In 1926 Pius XI condemned Action Française, the monarchist movement which had until this time operated with the support of a great many French Catholics. The Pope judged that it was folly for the French Church to continue to tie its fortunes to the unlikely dream of a monarchist restoration, and found the movement's tendency to defend the Catholic religion in merely utilitarian and nationalistic terms, as a vital contributing factor to the greatness and stability of France, unorthodox.

Although the condemnation caused great heartache for many French Catholics, most obeyed and Action Française never really recovered.

| Papal styles of Pope Pius XI |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Reference style | His Holiness |

| Spoken style | Your Holiness |

| Religious style | Holy Father |

| Posthumous style | None |

Relations with Italy and the Lateran Treaties

Pius XI aimed to end the long breach between the papacy and the Italian government and to gain recognition once more of the sovereign independence of the Holy See. This goal led to one of his signature achievements, the signing in 1929 of the Lateran Treaty with the Italian government and the establishment of an independent Vatican City State.

Most of the Papal States had been seized by the forces of King Victor Emmanuel II of Italy (1861 – 1878) in 1860 at the foundation of the modern unified Italian state, and the rest, including Rome, in 1870. The Papacy and the Italian Government had been at loggerheads ever since: the Popes had refused to recognise the Italian state's seizure of the Papal States, instead withdrawing to become prisoners in the Vatican, and the Italian government's policies had always been anti-clerical. Now Pius XI thought a compromise would be the best solution.

To bolster his own new regime, Benito Mussolini was also eager for an agreement. After years of negotiation, in 1929, the Pope supervised the signing of the Lateran Treaties with the Italian government. According to the terms of the first treaty, Vatican City was given sovereignty as an enclave of the city of Rome in return for the Vatican relinquishing its claim to the former territories of the Papal States. Pius XI thus became a head of state (albeit the smallest state in the world), the first Pope who could be termed as such since the Papal States fell after the unification of Italy in the 19th century. A second treaty, the concordat with Italy, recognised Roman Catholicism as the official state religion of Italy, gave the Church power over marriage law in Italy (ensuring the illegality of divorce), and restored Catholic religious teaching in all schools. In return, the clergy would not take part in politics. A third treaty provided financial compensation to the Vatican for the loss of the Papal States. During the reign of Pius XI this money was used for investments in the stock markets and real estate. To manage these investments, the Pope appointed the lay-person Bernadino Nogara, who through shrewd investing in stocks, gold, and futures markets, significantly increased the Catholic Church's financial holdings. However contrary to myth it did not create enormous Vatican wealth. The compensation was relatively modest, and most of the money from investments simply paid for the upkeep of the expensive-to-maintain stock of historic buildings in the Vatican which previously had been maintained through funds raised from the Papal States up until 1870.

The Vatican's relationship with Mussolini's government deteriorated drastically in the following years as Mussolini's totalitarian ambitions began to impinge more and more on the autonomy of the Church. For example, the Church's youth groups were dissolved in 1931 to allow Mussolini's fascist youth groups complete dominance.

As a consequence Pius issued the encyclical Non Abbiamo Bisogno in 1931, in which he criticized the idea of a totalitarian state and Mussolini's treatment of the Church. Relations with Mussolini continued to worsen throughout the remainder of Pius XI's pontificate.

Mussolini urged Pius to excommunicate Hitler as he thought it would render him less powerful in Catholic Austria and reduce the danger to Italy and wider Europe. The Vatican refused to comply and thereafter Mussolini began to work with Hitler, adopting his anti-semitic and race theories.[8]

Relations with Germany and the Concordat of 1933

Pius XI was eager to negotiate concordats with any country that was willing to do so, thinking that written treaties were the best way to protect the Church's rights against governments increasingly inclined to interfere in such matters. Twelve concordats were signed during his reign with various types of governments, including some German state governments, and with Austria. When Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany on 30 January 1933 and asked for a concordat, Pius XI accepted. Negotiations were conducted on his behalf by Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli, who later became Pope Pius XII (1939 – 1958). The Reichskonkordat was signed by Pacelli and by the German government in June 1933, and included guarantees of liberty for the Church, independence for Catholic organisations and youth groups, and religious teaching in schools.

In February 1936 Hitler sent Pius a telegram congratulating the Pope on the anniversary of his coronation but he responded with criticisms of what was happening in Germany, so much so that von Neurath the foreign secretary wanted to suppress it but Pius insisted it be forwarded.[9]

Syllabus against racism

In April 1938, the Sacred Congregation of seminaries and universities published at the request of Pius XI a syllabus condemning racist theories, a document which was sent to Catholic schools worldwide.

Mit Brennender Sorge

Pius XI responded to ever increasing Nazi hostility to Christianity by issuing in 1937 the encyclical Mit brennender Sorge condemning the Nazi ideology of racism and totalitarianism and Nazi violations of the concordat. Copies had to be smuggled into Germany so they could be read from the pulpit[10] The encyclical, the only one ever written in German, was addressed to German bishops and was read in all parishes of Germany. The actual writing of the text is credited to Munich Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber and to the Cardinal Secretary of State, Eugenio Pacelli, who later became Pope Pius XII.[11] There was no advance announcement of the encyclical, and its distribution was kept secret in an attempt to ensure the unhindered public reading of its contents in all the Catholic Churches of Germany.

This encyclical condemned particularly the paganism of National Socialist ideology, the myth of race and blood, and fallacies in the Nazi conception of God.

Whoever exalts race, or the people, or the State, or a particular form of State, or the depositories of power, or any other fundamental value of the human community — however necessary and honorable be their function in worldly things — whoever raises these notions above their standard value and divinizes them to an idolatrous level, distorts and perverts an order of the world planned and created by God; he is far from the true faith in God and from the concept of life which that faith upholds."[12]

Involvement with American efforts

Mother Katharine Drexel, who founded the American order of Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament for Indians and Colored People, corresponded with Pius XI, as she had with his papal predecessors. (In 1887, Pope Leo XIII had encouraged Katharine Drexel—then a young Philadelphia socialite— to do missionary work with America's disadvantaged people of color). In the early 1930s, Mother Drexel wrote Pius XI asking him to bless a publicity campaign to acquaint white Catholics with the needs of these disadvantaged races among them. An emissary had shown him photos of Xavier University, New Orleans, LA, which Mother Drexel had established to educate African-Americans at the highest level in the USA. Pius XI replied promptly, sending his blessing and encouragement. Upon his return, the emissary told Mother Katharine that the Holy Father said he had read the novel Uncle Tom's Cabin as a boy, and it had ignited his life-long concern for the American Negro.[13]

Conspiracy of Silence

While numerous German Catholics, who participated in the secret printing and distribution of the encylical Mit brennender Sorge, went to jail and concentration camps, the Western democracies remained silent, which Pope Pius XI labeled bitterly as "a conspiracy of silence".[14] As the extreme nature of Nazi racial antisemitism became obvious, and as Mussolini in the late 1930s began imitating Hitler's anti-Jewish race laws in Italy, Pius XI continued to make his position clear, both in Mit brennender Sorge and in a public address in the Vatican to Belgian pilgrims in 1938: "Mark well that in the Catholic Mass, Abraham is our Patriarch and forefather. Anti-Semitism is incompatible with the lofty thought which that fact expresses. It is a movement with which we Christians can have nothing to do. No, no, I say to you it is impossible for a Christian to take part in anti-Semitism. It is inadmissible. Through Christ and in Christ we are the spiritual progeny of Abraham. Spiritually, we [Christians] are all Semites"[15] These comments were subsequently published worldwide but had little resonance at the time in the secular media.[14] The "Conspiracy of Silence" included not only the silence of secular powers against the horrors of National Socialism but also their silence on the persecution of the Church in the Terrible Triangle. Despite these public comments, Pius was reported privately as suggesting that the Church's problems in the Soviet Union, Mexico and the Spanish Republic were, "reinforced by the anti-Christian spirit of Judaism".[16]

Terrible Triangle

| Part of a series of articles on 20th Century Persecutions of the Catholic Church |

|

|

Mexico Spain Germany China Vietnam Poland Eastern Europe Nicaragua El Salvador General |

|

Pius XI was faced with unprecedented persecution of the Catholic Church in Mexico and Spain and with the persecution of all Christians especially the Eastern Catholic Churches in the Soviet Union. He called this the Terrible Triangle[17]

Soviet Union

Worried by the persecution of Christians in the Soviet Union, Pius XI mandated Berlin nuncio Eugenio Pacelli to work secretly on diplomatic arrangements between the Vatican and the Soviet Union. Pacelli negotiated food shipments for Russia, and met with Soviet representatives including Foreign Minister Georgi Chicherin, who rejected any kind of religious education, the ordination of priests and bishops, but offered agreements without the points vital to the Vatican.[18] Despite Vatican pessimism and a lack of visible progress, Pacelli continued the secret negotiations, until Pius XI ordered them to be discontinued in 1927, because they generated no results and were dangerous to the Church, if made public.

The "harsh persecution short of total annihilation of the clergy, monks, and nuns and other people associated with the Church",[19] continued well into the 1930s. In addition to executing and exiling many clerics, monks and laymen, the confiscating of Church implements "for victims of famine" and the closing of churches were common.[20] Yet according to an official report based on the Census of 1936, some 55% of Soviet citizens identified themselves openly as religious, while others possibly concealed their belief.[20]

Mexico

During the pontificate of Pius XI, the Catholic Church was subjected to extreme persecutions in Mexico, which resulted in the death of over 5,000 priests, bishops and followers.[21] In the state of Tabasco the Church was in effect outlawed altogether. In his encyclical Iniquis Afflictisque[22] from 18 November 1926, Pope Pius protested against the slaughter and persecution. The United States intervened in 1929 and moderated an agreement.[21] The persecutions resumed in 1931. Pius XI condemned the Mexican government again in his 1932 encyclical Acerba Animi. Problems continued with reduced hostilities until 1940, when in the new pontificate of Pope Pius XII President Manuel Ávila Camacho returned the Mexican churches to the Catholic Church.[21]

There were 4,500 Mexican priests serving the Mexican people before the rebellion, in 1934, over 90% of them suffered persecution as only 334 priests were licensed by the government to serve fifteen million people. Excluding foreign religious, over 4,100 Mexican priests were eliminated by emigration, expulsion and assassination.[23][24] By 1935, 17 Mexican states were left with no priests at all.[25]

Spain

The Republican government which came to power in Spain in 1931 was strongly anti-clerical, secularising education, prohibiting religious education in the schools, and expelling the Jesuits from the country. On Pentecost 1932, Pope Pius XI protested against these measures and demanded restitution.

Syro-Malankara Catholic Church

Pope Pius XI accepted the Reunion Movement of Mar Ivanios along with four other members of the Malankara Orthodox Church in 1930. As a result of the Reunion Movement, the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church is in full communion with the Bishop of Rome and the Catholic Church.

Condemnation of racism

The fascist government in Italy had long abstained from copying the racial and anti-Semitic laws and regulations, which existed in Germany. This changed dramatically in 1938, the last year of the pontificate of Pius XI, when Italy introduced anti-Semitic legislation. The Pope asked Italy publicly to abstain from demeaning racist legislation, stating, that the term “race” is divisive but may be appropriate to differentiate animals.[26] The Catholic view would refer to "the unity of human society", which includes as many differences as music includes intonations. Italy, a civilized country, should not ape the barbarian German legislation.[27] In the same speech, he counter-attacked again the Italian government for attacking Catholic Action and even the papacy itself. Qui mange du Pape, en meurt - who eats from the pope, is dead![27] Peter Kent writes:

By the time of his death ... Pius XI had managed to orchestrate a swelling chorus of Church protests against the racial legislation and the ties that bound Italy to Germany. He had single-mindedly continued to denounce the evils of the nazi regime at every possible opportunity and feared above all else the re-opening of the rift between Church and State in his beloved Italy. He had, however, few tangible successes. There had been little improvement in the position of the Church in Germany and there was growing hostility to the Church in Italy on the part of the fascist regime. Almost the only positive result of the last years of his pontificate was a closer relationship with the liberal democracies and yet, even this was seen by many as representing a highly partisan stance on the part of the Pope. In the age of appeasement, the pugnacious obstinancy of Pius XI was held to be contributing more to the polarization of Europe than to its pacification. These reservations about the wisdom of Pius XI's policies were held by his closest and most loyal collaborator, Cardinal Pacelli ... Yet the policies followed by Pius XII soon proved to be very different from those of Pius XI. At heart, Pacelli ... was an appeaser. Pius XII rejected his predecessor's combative stance against the nazi and fascist regimes in favour of a politically disinterested position from which the Pope could act as a mediator to ensure European peace. Only if the papacy had an open and friendly relationship with all the great powers, could the Pope use his influence for the resolution of conflicts and the avoidance of war.

Humani Generis Unitas

The text of a possible encyclical Humani Generis Unitas, The Unity of the Human Society, that Pius XI commissioned to denounce racism in the USA, Europe and elsewhere, colonialism and the violent German nationalism was published by Georges Passelecq and Berard Suchecky under the title L'Encyclique Cachee De Pie XI[28]

Following Vatican custom, his successor Pope Pius XII, who according to the authors, was not aware of the text before the death of his predecessor,[29] chose not to publish this encyclical. However, his first encyclical Summi Pontificatus (12 October 1939), published after the beginning of World War II, has the identical title On the Unity of Human Society and uses many of the arguments of the text, avoiding all of the negative characterisation of the Jewish people and religion contained in the proposed text of the encyclical.[30] Summi Pontificatus sees Christianity being universalized and opposed to racial hostility and superiority. There are no real racial differences, because the human race forms a unity, because "one ancestor [God] made all nations to inhabit the whole earth".

Death and burial

Pope Pius had already been ill for some time when, on 25 November 1938, he suffered two heart attacks within several hours. He had serious breathing problems and had to stay in his apartment.[31] There he developed the idea of labelling two of his best bottles of wine to “my successor in the year 2000”.[31] It is not known if Pope John Paul II ever received them. He gave his last address to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, which he had founded. He spoke without prepared text on the relation between science and the Catholic religion. This is considered to have been his last major pontifical address.[32] A young priest tried to influence him to take his medicine, reminding him of the old Roman saying Principiis obsta (Resist the beginnings) but the Pope smiled and said, "you forgot the second part, sero medicina paratur, it’s too late for medicine". In February 1939, the situation of the Pontiff visibly degenerated. Pius had major pain and difficulties walking. When he tried to get out of bed, he was unable to do so, because of increased breathing problems. On 7 February, a team of several doctors announced to the papal staff that the Pontiff would soon depart from them.[33] He was now aided by this team of doctors, the professors Milani, Rocchi, Bonamone, Gemelli and Bianchi, specialists from all over Italy.[33] They informed Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli and Monsignor Giovanni Battista Montini that heart insufficiency combined with bronchial attacks had hopelessly complicated the already poor outlook. The Pope himself made plans for continued audiences with Domenico Tardini, as if he would recover within short time, although, because he was unable to breathe normally, he lost his ability to move or even to turn in his bed. His last words to those near him were spoken with clarity and firmness: My soul parts from you all in peace[34] Pope Pius XI died at 5:31 a.m. (Rome Time) of a third heart attack on 10 February 1939, aged 81. He was buried in the crypt at St. Peter's Basilica, in the main chapel, close to the Tomb of St. Peter.

Legacies

Pius XI will be remembered as the pope who reigned between the two great wars of the 20th century. The onetime librarian also reorganized the Vatican archives. Nevertheless, Pius XI was hardly a withdrawn and bookish figure. He was also a well known mountain climber with many peaks in the Alps named after him, he having been the first to scale them.[35]

Pius XI fought the two ascendant ideologies of communism and fascism.His success in fighting them was limited and there is much controversy over the concordats he entered with European regimes to improve the situation of the Catholic Church. At the outset, it was clear that he found communism to be the greater of the two evils but in his later years, there is no doubt that he was repelled by the momentum of Nazi Germany, not only in its opposition to the Catholic Church but also in the ferocity of its attacks on the Jewish people. Whatever the results of his activism, Pius XI did not sit by idly and was fully engaged until the end. A theological conservative, he strove to improve the condition of the Church, through the negotiation of the concordats (treaties) in Europe and to increase its strength worldwide through vigorous missionary work. He also reiterated the social teachings of Leo XIII in his encyclical Quadregesimo Anno, issued in 1931.

This pope was determined to increase the profile of the papacy from the time of his Urbi et Orbi (to the city and the world) blessing following his election, the first of its kind since Pius IX became a prisoner of the Vatican. (The blessing was delivered from the balcony overlooking St. Peter's Square and has become a tradition among the popes who succeeded him). After the Vatican had regained its status as a state in 1929, he flexed its muscles through the treaties he negotiated and by raising his voice in protest when the terms were violated, albeit to little avail.

A man of stature, he possessed an iron will and did not hesitate to assert his position. The strong-willed pontiff was succeeded by his charismatic Secretary of State, Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli (Pius XII), a diplomat who would continue Pius XI's struggle against Nazism and Fascism as a virtual prisoner in the Vatican during World War II.

A Chilean glacier bears Pius XI's name.[36] The Achille Ratti Climbing Club, based in the United Kingdom, was founded by Bishop T. B. Pearson in 1940 and was named after Monsignor Achille Ratti.

See also

- List of encyclicals of Pope Pius XI

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Quadragesimo Anno 44-52

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Quadragesimo Anno 114-115

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 see Casti Connubii

- ↑ Vatican website information re pontificate and policies of Pius XI

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Quadragesimo Anno 63-75

- ↑ Quadragesimo Anno 99 ff

- ↑ Quadragesimo Anno 109

- ↑ "The papacy, the Jews, and the Holocaust", Frank J. Coppa, p. 166-167, Catholic University of America Press, 2006, ISBN 081321449

- ↑ "The papacy, the Jews, and the Holocaust", Frank J. Coppa, p. 160, Catholic University Press of America, 2006, ISBN 081321449

- ↑ (Manners 2002, p. 374)

- ↑ August Franzen, Remigius Bäumer Papstgeschichte Herder Freiburg, 1988, p.394

- ↑ Mit Brennender Sorge, 8

- ↑ The Golden Door: The Life of Katharine Drexel, by Katherine Burton (P. J. Kenedy & Sons, New York, 1957, pg. 261)

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Franzen, 395

- ↑ Marchione 1997, p. 53.

- ↑ Geert, Mak (2004). In Europe:Travels through the 20th century. p. 295.

- ↑ Fontenelle, 164

- ↑ (Hansjakob Stehle, Die Ostpolitik des Vatikans, Piper, München, 1975, p.139-141

- ↑ Riasanovsky 617

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Riasanovsky 634

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Franzen 398

- ↑ Pope Pius XI (1926-11-18). "Iniquis afflictisque". http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/pius_xi/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-xi_enc_18111926_iniquis-afflictisque_en.html. Retrieved 2009-10-21.

- ↑ Scheina, Robert L. Latin America's Wars: The Age of the Caudillo, 1791-1899 p. 33 (2003 Brassey's) ISBN 1574884522

- ↑ Van Hove, Brian Blood-Drenched Altars Faith & Reason 1994

- ↑ Ruiz, Ramón Eduardo Triumphs and Tragedy: A History of the Mexican People p.393 (1993 W. W. Norton & Company) ISBN 0393310663

- ↑ Confalioneri 351

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Confalioneri 352

- ↑ La Decouverte, Paris 1995

- ↑ Letter of Father Maher to Father La Farge, 16 March 1939

- ↑ Summi Pontificatus

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Confalonieri 356

- ↑ Confalonieri 358

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Confalonieri 365

- ↑ Confalonieri 373

- ↑ The New York Times. Tuesday, 7th February, 1922, Page 1 (continued on page 3), 3059 words.

- ↑ Durango Herald report on glacier bearing Pius XI's name

Sources

- Confalonieri, Carlo. PIO XI - Visto Da Vicino. 1957. Translated by: Regis N. Barwig. PIUS XI - A Close Up. 1975. Altadena, California: The Benzinger Sisters Press.

- Manners, John (2002). The Oxford History of Christianity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 770 pages. ISBN 0192803360.

- Lucio D'Orazi, Il Coraggio Della Verita Vita do Pio XI, Edizioni logos,Roma, 1989

- Mrg R Fontenelle Seine Heiligkeit Pius XI. Alsactia, France, 1939

- Marchione, Margherita (1997). Yours Is a Precious Witness: Memoirs of Jews and Catholics in Wartime Italy. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press. pp. 272 pages. ISBN 0809104857.

- Josef Schmidlin Papstgeschichte, Vol I-IV, Köstel-Pusztet München, 1922–1939

- Morgan, Thomas B. A Reporter At The Papal Court - A Narrative of the Reign of Pope Pius XI. 1937. New York: Longmans, Green and Co.

External links

- Vatican Website for Pope Pius XI

- Catholic Forum Biography

- Vatican Museum Biography

- Pius XI and the mystery of the disapperead encyclical at YouTube

- Pope Benedict XVI opens the Archives for the pontificate (1922–1939) of Pope Pius XI - VATICAN CITY, July 2, 2006 "...researchers will be able to consult all the documents of the period kept in the different series of archives of the Holy See, primarily in the Vatican Secret Archives and the Archive of the Second Section of the Secretariat of State...."

| Catholic Church titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Andrea Ferrari |

Archbishop of Milan 1921 – 1922 |

Succeeded by Eugenio Tosi |

| Preceded by Benedict XV |

Pope 1922–1939 |

Succeeded by Pius XII |

| Awards and achievements | ||

| Preceded by Carter Glass |

Cover of Time Magazine 16 June 1924 |

Succeeded by Hiram W. Evans |